Why do I build gypsy wagons?

The first answer that comes to mind, which is probably the one closest to the truth, is an answer essentially the opposite to how mountaineers often reply when asked why they climb a mountain (i,e, “Because its there.”). In my case, I’ve always wanted to build gypsy caravans because they are not there!

I have long been fascinated with the traveling lifestyle, with life lived mostly outdoors, lived close to the edge---I life I lived for a decade or so of my life. I learned that if you could live such a life in company with a cozy and enchanting conveyance in the form of a highly developed folk craft, then so much the better.

For me, that conveyance was the English or Irish gypsy caravan (or Vardo in the Romany language). Ever since having first seen highly romanticized illustrations of them in children’s books (see “Wind in the Willows” for starters), then finding murky black and white photos of them on the road at the end of the 19th century, and finally getting my hands on glorious color photos of restored versions at Appleby Faire in England, I knew I had to have one. I also knew that the only way I would ever get my hands on one would be to get my hands to build one.

Starting in the late 1970’s I built, and traveled in, a very simple version affixed to the frame of a 1940 Ford 1-ton pickup.

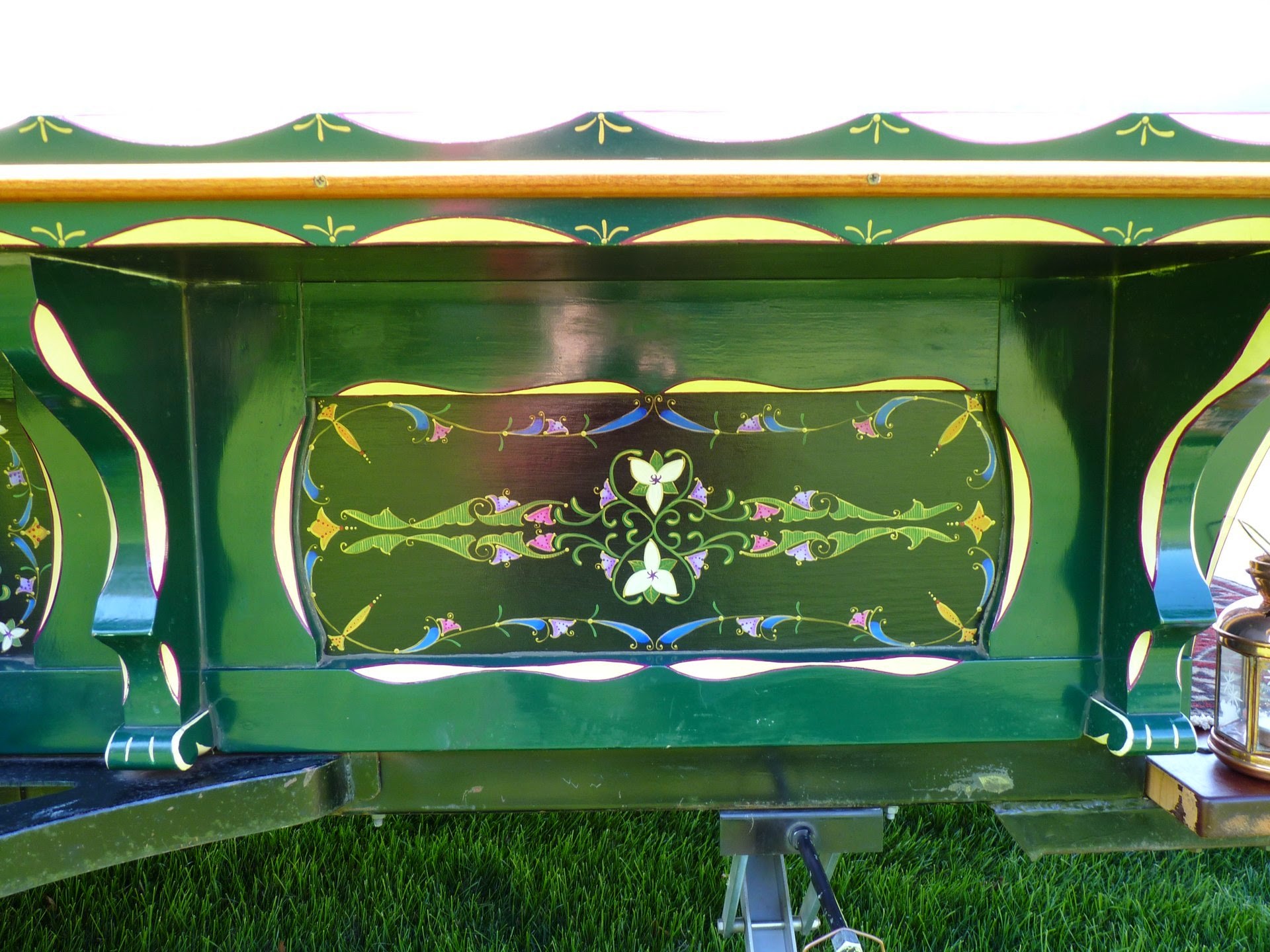

After moving to the Northwest, I embarked on building more authentically designed and detailed vardos, culminating in the “Trillium” completed in 2007. This wagon closely reproduced the look of a “bow top” style caravan that was produced by Bill Wright’s carriage shop in Leeds, England in the late 19th century.

Like most of my other wagons, the Trillium was built in collaboration with several other artists: a metal worker for the welded steel frame and some of the decorative brackets; a graphic artist for the panel art and lining out; and a stained glass maker for the windows. The current owner provided much of the fabric work of the interior decor.

Materials throughout this and all my other wagons are marine grade: Honduras mahogany for the framework (mostly pinned tenon and bridle joints); Port Orford cedar for the tongue and groove siding; Sitka spruce for roof framing; Egyptian canvas sailcloth for the cover; marine grade oil enamel paints and bedding compounds; stainless steel fasteners and copper rove and rivets.

Joinery throughout, include interior fittings, is built to traditional joiner’s (rather than cabinetmaker’s) standards. That is, all the joints are mechanically interlocked and therefore don’t rely on glue or fasteners to bear loads.

None of my wagons were designed to be horse-drawn. I don’t know horses, and I don’t know how I would convince the beast to pull my wagon around the highways and byways of America. But I do know how to pull trailers behind my pickup truck, so I built my wagons to be roadworthy for travel at highway speeds.

Whether traveling at 4 miles or 400 miles a day, however, these wagons are the conveyances of dreams-come-true. They are a folk-craft of the hand that takes the heart home.